First Consensus Meeting on Menopause in the East Asian Region

Risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy

Duong Thi Cuong

Institute for the Protection of the Mother and Newborn, Hanoi, Vietnam

The menopause is the final menstrual period which indicates the complete cessation of ovarian function. The hypo-oestrogenic state at the menopause is manifested in many women by signs and symptoms of hormonal deficiency in tissues containing oestrogen receptors such as the ovary, endometrium, vaginal epithelium, urethra and skin. The most common complaints are vasomotor disturbances characterized by hot flushes, genital atrophy, psychological symptoms and an increased risk of osteoporosis. These changes have been called the menopausal syndrome.

Vasomotor flushes (hot flushes) may begin in the perimenopausal period months or years prior to the menopause. The duration of the flush can vary from a few seconds to minutes, lasting sometimes as long as an hour, and may recur as often as every 30 min. Flushes appear to be more severe at times of stress and more frequent and severe at night, hence the term night sweats.

A number of anatomical changes in the genitourinary tract result from the decline in oestrogen in the menopausal woman [1, 2]. With a decrease in glycogen in the vaginal epithelium, there is increased growth of other vaginal flora and a consequent susceptibility to irritation, trauma and infection. A loss of bladder sphincter tone at the menopause is characterized by recurrent bacterial urethritis and dysuria, frequency, urgency, nocturia and dribbling. Hypo-oestrogenaemia accelerates ageing of the skin, which becomes thin and dry.

Postmenopausal osteoporosis is characterized by a progressive loss of bone mass, resulting in inadequate mechanical support and an increased risk of fracture. The loss of bone mass correlates with the duration of oestrogen deficiency. The hypo-oestrogenic state involves cardiovascular and lipid changes which may be a significant factor in the development of ischaemic heart disease.

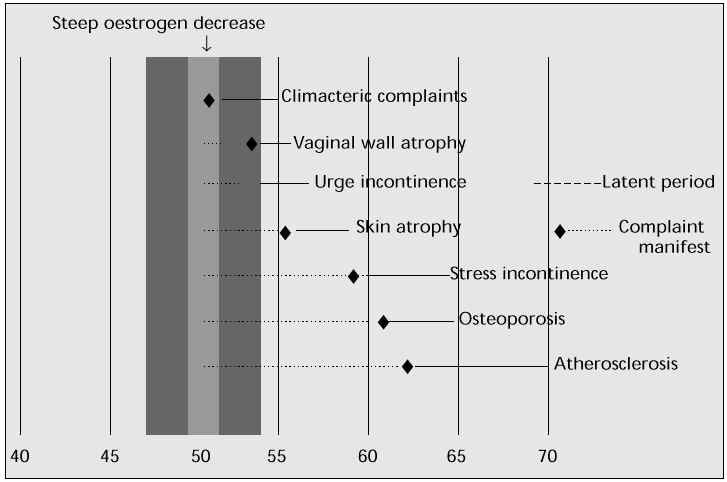

The hypo-oestrogenic state of the menopause can also cause psychological and other symptoms [3]. Complaints of fatigue, nervousness, headache, insomnia, depression, irritability, joint and muscle pain, forgetfulness, inability to concentrate, dizziness and palpitations are all related to the menopausal syndrome. These symptoms can be attributed to the sleep deprivation resulting from frequent night sweats. Another complaint is the decrease in sexual response and a decline in libido. Figure 1 shows the major symptoms of oestrogen deficiency [4].

Fig. 1: Age at onset of oestrogen deficiency symptoms [4].

Hormone replacement therapy

The menopause is a normal and natural event in the female life span. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has been available for 25 years and although it may provide benefits for many women, not all women want or need to use it. Many elderly women, especially those in Asian countries, enjoy an excellent qualify of life without HRT.

Many women and doctors consider the menopause and the cessation of oestrogen production as natural events for which medical treatment is not necessary. However, by persisting in this view and maintaining their fear of hormones, they ignore the enormous progress that has been made over the past decade as regards the possible wanted and unwanted effects of HRT [5].

When treating perimenopausal women with hormones, individual assessments are obviously necessary. For a woman with typical vasomotor symptoms it is relatively straightforward: a short course of oestrogens is usually sufficient; treatment can be halted if the symptoms do not recur on discontinuation of therapy [6].

For complaints of vaginal atrophy, the decision to use HRT is again straightforward, but the process of atrophy will start as soon as therapy is stopped, so treatment needs to be long-term.

For postmenopausal urinary incontinence, oestrogen alone will not be curative. Other factors are involved such as weakness of the pelvic floor in stress incontinence or insufficient nervous control over micturition reflexes in urge incontinence. The best therapeutic option is to combine HRT with other medication or surgery if necessary.

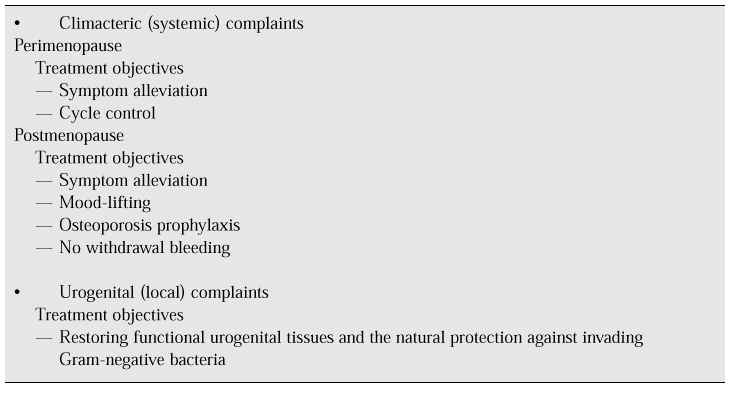

Urinary tract infections cannot be treated with oestrogen, but their recurrence can be prevented with HRT because oestrogen treatment has a positive effect on the bacterial composition of the vaginal flora and vaginal pH. Table I illustrates the use of HRT for climacteric complaints.

Table I: Treatment uses of HRT.

HRT prevents postmenopausal bone loss for women at increased risk of osteoporosis or cardiovascular disorders. Because bone loss can begin 4 years before the menopause, women aged between 40 and 50 with irregular cycles have 10% lower bone mineral density on average than women of the same age with regular cycles. If oestrogen is to be given to prevent osteoporosis, it should be started when the menstrual cycles become irregular.

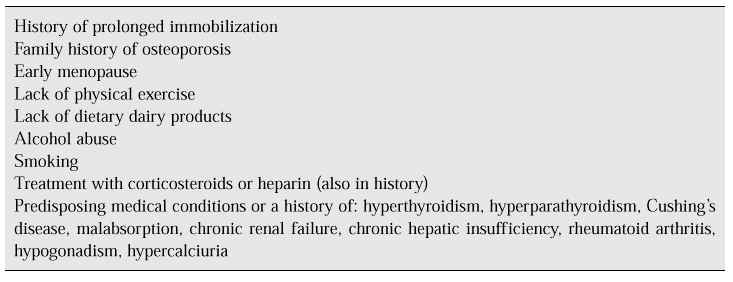

Lindsay [7] expressed the opinion that screening should be carried out to assess risk factors for osteoporosis (Table II). When one or more such factors are present, bone density measurement should be performed. Women at risk after this evaluation should be given oestrogen replacement therapy for the rest of their lives, since the protective action of oestrogens on bone density is effective only while they are being taken.

Table II: Risk factors for osteoporosis.

It has been demonstrated that oestrogens protect against cardiovascular disorders in postmenopausal women, giving a reduction in the incidence of coronary heart disease and strokes of 50–70%. This protective action seems to lie in the positive effect that oestrogen has on lipid metabolism by increasing serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and decreasing those of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. To overcome the effect of unopposed oestrogen therapy on the endometrium, progestogens are now usually given in combination with oestrogens, but the addition of a progestogen may diminish or take away the protective effect of oestrogen on cardiovascular risk [8].

Evaluation of patients on HRT

Before instituting hormonal therapy, a complete history and physical examination should be taken. This should include:

— stool guaiac,

— Pap smear,

— baseline mammogram,

— sequential multiple analyser,

— fasting cholesterol,

— triglycerides,

— glucose concentration,

— liver function test (with past history of liver disease),

— endometrial biopsy (in high-risk groups).

Once HRT is initiated, patients should be evaluated after 4–6 weeks to adjust the dosage if necessary and to evaluate any side effects and complications. Oestrogen should be discontinued immediately if patients develop severe headaches, visual changes, chest pain or symptoms of thrombophlebitis. A biopsy should be performed immediately in any woman who develops abnormal bleeding. Breast and pelvic examination, blood pressure monitoring, Pap smear and stool guaiac should be repeated at least yearly. Periodic mammograms should also be performed.

In summary, for many women HRT is not only protective against the onset of osteoporosis, the symptoms of menopausal syndrome, atrophic changes and probably atherosclerosis, but also improves their mental well-being and quality of life [9]

Benefits of hormone replacement therapy

Short-term therapy

Hot flushes and night sweats

Hot flushes and night sweats are thermoregulatory disturbances characteristic of the menopause. Hot flushes may be more severe in women who undergo bilateral oophorectomy. Hot flushes are a complaint of many women but they can be ameliorated or abolished by oestrogen administration at the lowest dose possible with or without progestogens. Patients should be supervised medically and specific contraindications to oestrogen therapy observed. Since in most cases hot flushes decline in frequency and intensity with time, therapy can usually be of relatively short duration, thus avoiding or reducing the possible risks of cancer, particularly endometrial cancer. If oestrogens are given continuously, periodic progestogen administration may reduce the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia [10].

The role of exercise is also important. Exercise seems to protect against depression and reduce the frequency of vasomotor symptoms.

Postmenopausal oestrogen deficiency

Postmenopausal oestrogen deficiency results in atrophic changes in the lower genitourinary tract. These may cause vaginal symptoms such as vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, itching or discharge, or urinary symptoms such as frequency, urgency and dysuria. Intravaginal oestrogen replacement therapy can rapidly alleviate these symptoms. For many women, vaginal complaints completely disappear often within 2 weeks of treatment. HRT may improve urinary symptoms, but it is not of proven benefit in the treatment of genuine stress incontinence.

The short-term local administration of oestrogen in addition to systemic treatment is of benefit for urogenital symptoms.

Long-term therapy

Osteoporosis

Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis are the major indications of HRT due to the ability of oestrogens to delay bone loss, decreasing the risk of fracture. However, the World Health Organization does not recommend the universal or widespread use of oestrogen for the prevention of osteoporosis or fractures, for at least two reasons. Firstly, the fact that bone loss sufficient to cause fractures affects only 25% of the population; and secondly, factors other than oestrogens, such as activity, calcium intake, diet, vitamin D, smoking and alcohol may also play a role in osteoporosis.

The most important aspect of osteoporosis management is prevention of the disease. A high peak bone mass before the menopause protects against the development of osteoporosis. For individuals at high risk such as women who have been oophorectomized at a young age, HRT may be used to prevent osteoporosis. An adequate dietary calcium intake should also be encouraged [11, 12].

Cardiovascular disease

The incidence of cardiovascular disease in East Asia is currently lower than that in the West but it is nevertheless on the increase. This is related to an increase in longevity, a more atherogenic lipid profile (diet-related), an increase in diabetes mellitus and an increase in obesity.

The administration of oestrogen to postmenopausal women has been shown to result in the development of a less atherogenic lipid profile. HRT administration reduces lipoprotein concentration and produces an increase in blood flow. Hence the postmenopausal use of oestrogen with or without a progestogen is expected to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, especially in women with hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and in those who smoke or lead a sedentary life. However, the use of oestrogen for prophylactic purposes needs to be long-term, but first, subjects must be thoroughly assessed before a decision to begin HRT is made. The presence or absence of a uterus and benign breast disease are important factors. Prophylaxis should also include attention to diet and weight control, physical activity, control of blood pressure and a reduction in sodium intake and smoking [13, 14].

Alzheimer’s disease

Due to the increase in female longevity, the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease is also expected to increase. There are convincing data to suggest that the use of HRT delays the onset and reduces the risk of Alzheimer’s disease as well as delaying its progression.

Risks of hormone replacement therapy

The decision to place a woman on HRT must be made on an individual basis after weighing all the risks and benefits. Some complications of exogenous oestrogen therapy are listed below.

Gallbladder disease

There is an increased risk of cholelithiasis by increasing cholesterol saturation of the bile. The risk of gallbladder disease is increased more than 2.5-fold in women on HRT.

Endometrial cancer

There is a risk of the development of adenocarcinoma of the endometrium if oestrogen is given without the addition of a progestogen, the risk being a 4- to 12-fold increased incidence, especially when oestrogens are used for more than 2–3 years. There is a consistent progression in the endometrium from hyperplasia to hyperplasia with atypia and then to adenocarcinoma. The carcinoma associated with oestrogen use is low-grade, well differentiated and can usually be treated by simple hysterectomy [15].

Several studies have reported that oestrogen-induced hyperplasia and carcinoma of the endometrium can be prevented by the addition of a progestogen. Some data suggest that duration of therapy may be more important than dose with regard to hyperplasia. Therefore women with an intact uterus should always receive combined oestrogen/progestogen therapy. Before commencement of HRT, an endometrial biopsy is not necessary if the woman is amenorrhoeic. An endometrial biopsy is indicated, however, in the presence of any abnormal bleeding after the use of HRT. Transvaginal ultrasonography to measure the endometrial thickness is considered insufficient on its own to exclude an endometrial pathology [15, 16].

Breast cancer

Until now, in East Asian countries, the possible risk of breast cancer, along with the cost and inconvenience of HRT treatment, has been one of the main factors checking its use. Breast cancer is a prevalent malignancy among women, but the aetiologic role of oestrogen in breast cancer is unknown. Some studies have found a significantly higher relative risk of 3–4 among hormone users, while others have claimed that there is no significant increase in the risk of breast cancer associated with the use of HRT. It is currently agreed that short-term use of HRT does not increase the risk of developing breast cancer. However, the data on the long-term use of HRT and the risk of breast cancer are contradictory [17]. A breast examination and mammography with or without ultrasonography should be done prior to the institution of HRT and it is advisable to follow up these women closely at appropriate intervals thereafter.

Other risks

Other risks of HRT are the precipitation of myocardial infarction, hypertension, changes in liver function and thromboembolic problems. These complications are influenced by oestrogen dose, duration of therapy, smoking, genetic susceptibility, concomitant disease and age.

Contraindications to HRT include uncontrolled hypertension, unexplained vaginal bleeding, liver disease, active thromboembolic disease, porphyria, recent endometrial or breast cancer, and existing cardiovascular disease [18].

Relative contraindications include gallbladder disease, pancreatitis, leiomyomas, endometriosis, migraine, seizure, hypertriglyceridaemia, endometrial cancer, and a strong family history of breast cancer. In most instances, the level of oestrogen used in HRT is not sufficient to stimulate endometriosis and leiomyomas, but the decision to give HRT to women in these categories must be based on the severity of the symptoms and the circumstances. There is no contraindication to the use of HRT in women with a history of cervical or ovarian carcinoma, nor does the use of HRT increase the risk of recurrence of breast cancer [19].

The patient should be well informed of the potential adverse effects of treatment and must clearly believe that the benefits to her outweigh the risks. The ultimate decision should always rest with the patient. Notwithstanding, the available data suggest that the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks.

Therapeutic modalities

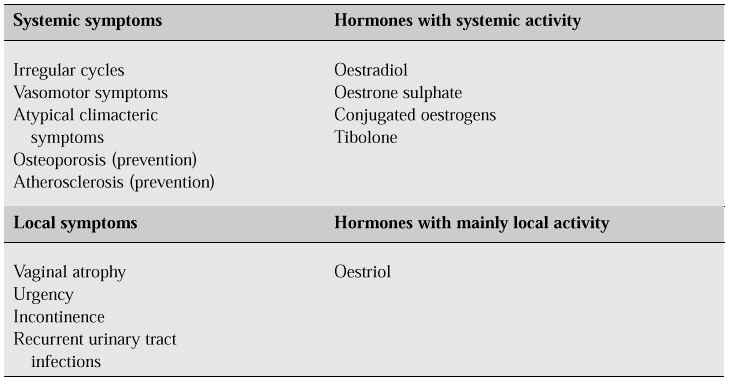

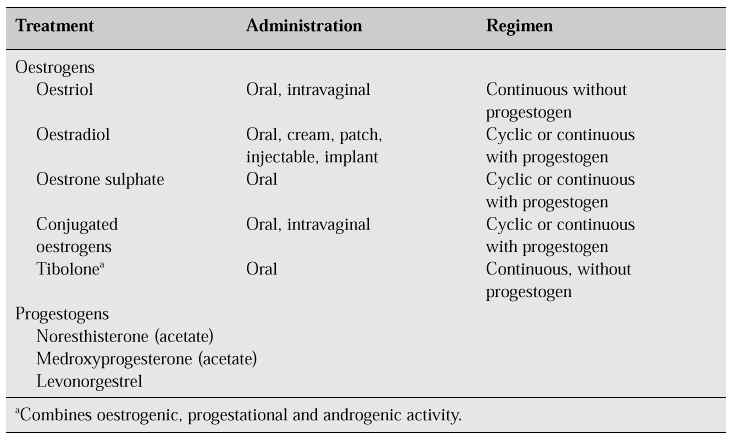

There are several classes of oestrogens. Naturally occurring oestrogens, including 17a-oestradiol, oestrone sulphate, oestriol and conjugated oestrogens, are those generally given for replacement therapy (Table III). Synthetic oestrogens including ethinyloestradiol, and the non-steroidal oestrogens including diethylstilbestrol are not generally used for HRT because of the risk of severe derangements of liver function [21].

Table III: Systemic and local symptoms and their treatment [20].

Oestrogen can be administered through a variety of routes including oral, intramuscular, transdermal (jelly or patch), subcutaneous (implants), nasal and intravaginal. Nasal sprays allow direct and rapid absorption. Intramuscular injection is convenient as it requires infrequent administration, but immediate reversal is impossible and tolerance may develop. Moreover, very high circulating levels of oestrogen may be achieved soon after administration. Subcutaneous pellets also give sustained release, but immediate reversal may not be possible because retrieval of the pellet is difficult. Oestrogen creams can be used but require a wide area of application. Transdermal patches allow direct absorption but the effect is not sustained, therefore the patch must be worn continually and reapplied at appropriate intervals. The most frequent complication of transdermal delivery is significant skin irritation. Vaginal suppositories and creams permit direct absorption but are unacceptable to many women. The oral route is the most convenient but is the only mode of delivery that significantly affects the liver. Other forms are currently being investigated, including vaginal rings containing oestrogen and sublingual tablets [22, 23].

There is no superiority of benefit or excess risk attributable to any specific oestrogen. The most commonly prescribed oestrogen is oral conjugated oestrogen which at a daily dose of 0.625 mg is effective in eliminating complaints in most postmenopausal women. Higher dosages may be necessary when first starting replacement therapy in women with severe symptoms.

Oestrogen administration is associated with a number of side effects that may affect compliance: breast tenderness, nausea, vomiting, weight gain of up to 5 lb, fluid retention and heartburn. The most frequent complaint with HRT is uterine bleeding, and the frequency of irregular bleeding is related to the oestrogen dose.

The use of progestogen to modify oestrogen action on target tissues has been mentioned with respect to reduction of the risks of oestrogen overstimulation and carcinogenesis in the endometrium. Progestogen has been shown to be effective as a substitute for oestrogen in relieving hot flushes.

In many developing countries such as Vietnam, the use of combined oral contraceptives instead of oestrogens alone to treat peri- and postmenopausal women is popular because of their convenience and low cost. A new type of steroid, tibolone, has recently become available. Tibolone combines oestrogenic, progestogenic and androgenic effects and seems to have a specific mood-lifting effect and also to increase libido [6, 24].

There are four different types of treatment regimens, namely cyclic and continuous, with or without progestogens (Table IV). One of the most widely prescribed (cyclic regimen) for women with an intact uterus is: oestrogen from day 1 to day 25 with the addition of progestogen from day 13 to day 25 with a 4- to 7-day medication-free interval during which withdrawal bleeding occurs [25, 26]. Another more popular regimen is continuous oestrogen therapy (continuous regimen) with a combination of oestrogen and progestogen which is taken every day without interruption. Bleeding is no more frequent with this regimen, with the added advantage that it is easier for the patient to remember.

Table IV: Hormonal treatments available for menopause-related complaints.

How long therapy of postmenopausal or oophorectomized women should continue is unknown. Duration of therapy can be based on the response of the patient and the reason for giving the HRT.

Oral HRT is widely accepted, but this route entails first liver passage which can affect a number of metabolic processes as well as the coagulation fibrinolytic system. It is therefore believed that it is better to avoid the metabolic effects of first liver passage. This has resulted in the development of oestrogen jellies, transdermal patches, injectables and implants. Fewer metabolic effects are seen with these forms of administration.

The effect on the liver of administering a non-oral oestrogen and an oral progestogen is, however, to produce changes in lipid metabolism related to increased risk of cardiovascular disease [27].

Intravaginal administration of oestriol and conjugated oestrogens has a different rationale. Oestrogen administered via the vaginal route has an immediate effect on the vaginal tissues and can be used in lower doses to achieve the same effect as when administered orally.

The choice between oral and non-oral administration also depends on factors related to patient compliance. Oral administration requires daily tablet-taking; the transdermal patch needs to be changed once or twice a week and entails possible skin irritation (particularly in hot, humid climates); injectables are active for 1–3 months and subdermal oestradiol implants for 6 months, but both have the disadvantage that they are invasive procedures. For some women, intravaginal administration of an oestrogen cream or pessary is unacceptable. Each form of administration has its advantages and disadvantages, and an individual choice can be made only after discussion with the patient.

Conclusion

The peri- and postmenopausal periods of life are part of the normal ageing process which in itself does not require therapeutic intervention. The majority of women should not necessarily anticipate a need for treatment of these spontaneously occurring endocrine changes. However, before opting to use HRT, all women should be counselled with regard to a healthy life style to enable them to adopt a diet low in fat and cholesterol and containing adequate calcium and vitamin D, to exercise, give up smoking, reduce alcohol intake and excessive weight gain. The decision to use or not to use HRT is not irrevocable; it can be reversed at any time.

In the future, it is expected that more and better new products and treatment regimens will be available which will not reintroduce bleeding and which will be therefore more acceptable.

According to Van Keep [4], the ideal medication for the menopausal woman should effectively suppress climacteric symptoms, protect against urogenital atrophy, have a preventive effect on postmenopausal bone loss, not reintroduce menstrual bleeding, have no unfavourable effect on lipid metabolism, contribute to her psychosocial functioning, and reduce the risk of cancer of the ovary, endometrium and breast.

References

1. Baudet JH, Seguy B. La ménopause. Gynecologie. Paris: Maloine, 1987; 14: 155.

2. Gass M, Mezrow G, Rebar RW. The menopause. Gynecol Obstet 1995; 24: 1–23.

3. Brumsted JR. Menstruation and disorders of menstrual function. In: Danforth’s obstetrics and gynecology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1994; 665.

4. Van Keep PA. The history and rationale of hormone replacement therapy. Maturitas 1990; 12: 163–70.

5. Salomon B. La pathologie genitale de la menopause. Rev MŽd Paris 1972; 24: 1605.

6. Cuong DT, Lieu NK, Tien NV. Hormonotherapie en gynecologie. In: Manuel de gynecologie. Hanoi: Medical Publication, 1992; 123.

7. Lindsay R. The menopause and osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87 (Suppl 2): 16–9.

8. Netter A, Gorins A. Menopause — gynecologie, reproduction. Paris: Flammarion, 1975; 45.

9. Hammond CB. Menopause and hormone replacement therapy: an overview. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87 (Suppl 2): 2–15.

10. Rekers H. Mastering the menopause. In: Burger HG, et al., ed. A portrait of the menopause: expert reports on medical and therapeutic strategies for the 1990s. Carnforth, UK: Parthenon, 1991; 23–43.

11. Gallagher JC, Nordin BEC. Hormones et mŽtabolisme calcique chez les femmes menopausees. In: ActualitŽs GynŽcologiques. Paris: Masson, 1974; 4: 113.

12. Hammond CB. Climacteric. In: Danforth’s obstetrics and gynecology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1994; 771.

13. Bardin CW, Swerdloff RS, Santen RJ. Androgens: risks and benefits. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991; 73: 4–7.

14. Gelety TJ, Judd HL. Menopause: new indications and management strategies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 1992; 4: 346–53.

15. Goodman L, Awwad J, Marc K. Schiff I. Continuous combined hormonal replacement therapy and the risk of endometrial cancer — preliminary report. Menopause 1994; 1: 57–9..

16. Smith DC, Prentice R, Thompson DJ, Herrmann WL. Association of exogenous estrogen and endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med 1975; 293: 1164–7.

17. Speroff L. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87 (Suppl 2): 44–54.

18. Tepper R, Geldberger S, May JY et al. Hormonal replacement therapy in postmenopausal women and cardiovascular disease: an overview. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1992; 47: 426–31.

19. Thang DV. Menopause et ses troubles. In: Leçons de gynecologie obstetrique. Hanoi: Medical Publication, 1971; 84.

20. Von Schoultz B. Hormone replacement therapy: the T concept. Presented at: The 6th International Congress on the Menopause, Bangkok, 1990.

21. Hahn RG. Compliance considerations with oestrogen replacement: withdrawal bleeding and other factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989; 161: 1854–8.

22. Millet D. Physiologie de la mŽnopause. Vie MŽd 1971; 40: 4887.

23. Prough SG, Aksel S, Wiebe RH et al. Continuous oestrogen/progestin therapy in menopause. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987; 157: 1449–53.

24. Payer L. The menopause in various cultures. In: A portrait of the menopause. Carnforth, UK: Parthenon, 1991; 3.

25. Ettinger B, Selby J, Citron JT, et al. Cyclic hormone replacement therapy using quarterly progestin. Obstet Gynecol 1994; 83: 693–700.

26. Weinstein L. Efficacy of a continuous oestrogen-progestin regimen in the menopausal patient. Obstet Gynecol 1987; 69: 929–32.

27. Robert HG. Menopause et climatere. In: Precis de gynecologie. Paris: Flammarion, 1979; 176.

Recommended reading

1. Surgically confirmed gallbladder disease, venous thromboembolism, and breast tumors in relation to postmenopausal estrogen therapy. Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. N Engl J Med 1974; 290: 15–9.

2. World Health Organization. Research on the menopause. Tech Rep Ser 1981; 670.

3. Birkhäuser MH, Rozenbaum H, eds. Menopause. European Consensus Development Conference on Menopause. Montreux: Editions Eska, 1996.