First Consensus Meeting on Menopause in the East Asian Region

Contraception in the perimenopause

C.J. Haines (1), F. Lüdicke (2)

(1) Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, New Territories, Hong Kong; (2) University Hospital Geneva, Switzerland

Introduction

The perimenopause is the phase in the ageing process in which a woman passes from the reproductive to the non-reproductive stage. During this time she reaches the menopause, a term which originates from the Greek words men and pauo, which mean ‘month’ and ‘stop’. The menopause has been defined as the permanent cessation of menstruation resulting from loss of ovarian follicular activity [1]. The perimenopause is the time preceding the menopause when the endocrinological, biological and clinical features of approaching menopause begin, and this definition also includes the first year after the menopause [2]. During these perimenopausal years, menstrual cycles tend to become irregular, but although there is a decline in natural fertility, contraception is still necessary if unplanned pregnancies are to be avoided. The importance of contraception for the older woman is emphasized by figures from the USA which show that the highest percentages of unplanned pregnancies have been in adolescents and in women older than 35 years [3].

Women approaching the menopause often have contraceptive requirements which differ from those of younger women, but the provision of effective contraception remains equally important. Pregnancies in the late reproductive years are associated with a higher maternal as well as perinatal mortality and a greater incidence of fetal malformation. Medical disorders such as diabetes mellitus and essential hypertension are more common, and these conditions increase the risk to both the mother and fetus. If pregnancy termination is chosen, this can expose the couple to psychological trauma and carries with it significant medical risk. Various gynaecological pathologies such as uterine fibroids are also more frequently encountered in perimenopausal women, and anovulatory cycles during the perimenopause may cause dysfunctional uterine bleeding or predispose to endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma.

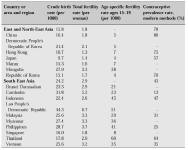

This article describes some of the theoretical advantages and disadvantages of various methods of contraception for perimenopausal women. What should be borne in mind, however, is that one of the greatest problems faced by many of the developing countries is the provision of realistic access to family planning services [4]. Figures for the prevalence rate of different types of contraceptive methods used in Asia are shown in Table I. The goals of an effective service should be to offer a wide variety of contraceptive methods from easily accessible centres staffed by educated personnel. It is also essential that the cost of contraceptives should not be prohibitive. The cost to the consumer varies widely between countries and is partly dependent upon marketing strategies and financial subsidies provided through the health care systems.

Table I: The prevalence rate of different types of contraceptive methods used in Asia. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Population Division ESCAP Population Sheet 1997.

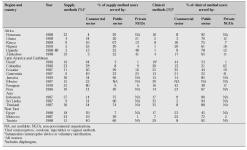

The contributions to contraception made by different categories of health care providers in selected developing countries are shown in Table II. In many of these areas, the main providers of contraception are not public institutions, which suggests that cost may be an important factor in determining the number of women who can receive the contraceptive method of their choice in these areas.

Table II: Sources of family planning methods for married women of reproductive age as reported in Demographic and Health Surveys, 1986– 1990 [5].

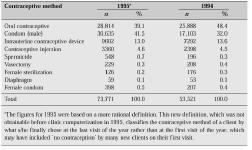

The popularity of different methods is not only influenced by cost, but also by the variety of methods which are offered by the regional family planning services. As an example, a summary of the frequency of use of different types of contraception offered by the Family Planning Association of Hong Kong for the years 1994–95 is presented in Table III.

Table III: Hong Kong Family Planning Association Contraceptive methods used by all birth con-trol clients in 1994 and 1995 [6].

From this table, it would appear that permanent methods of contraception are rarely used in this population, but some organizations such as the Family Planning Association can offer reversible methods of contraception more readily than permanent methods. In 1994 there were also approximately 2143 admissions to Hong Kong hospitals for female sterilization. Although these data are incomplete, 1421 sterilization procedures were recorded using tubal ligation and 896 by a laparoscopic method [7]. The discrepancy in these figures may have arisen because this audit did not determine the number of procedures in which a sterilization as well as another gynaecological procedure were performed simultaneously. However, the point is still made that the frequency of use of each method is affected by its availability.

Whilst continuing efforts are being made to provide safer, more reliable and more acceptable methods of contraception, improvements in family planning services can also be achieved by satisfying the criteria of easy availability and low cost. This will enable more women to be protected against unplanned and unwanted pregnancies.

Hormonal changes during the perimenopause

During the reproductive life span the number of ovarian primordial follicles steadily diminishes, but after approximately 40 years of age the rate at which follicles are lost starts to accelerate [8]. Despite the reduction in the number of follicles, ovulation continues in up to 98% of women over the age of 40 who have regular menstrual cycles [9], which emphasizes the necessity for the continued use of contraception.

Even though regular ovulatory cycles may be maintained, changes occur in the regulators of the hypothalamic-pituitary ovarian axis well before the time of ovarian failure. The earliest change is an increase in follicular phase concentrations of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Secretion of FSH is under the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus and is subject to negative feedback from the ovary through both inhibin and oestradiol. With advancing age there is increasingly irregular follicular maturation, and FSH concentrations rise due to a decrease in negative feedback. Whilst concentrations of oestradiol and progesterone are not significantly different from those of younger women, concentrations of FSH increase by up to three times in women above 35 years of age, although luteinizing hormone (LH) concentrations remain either normal or become only slightly elevated [10]. As a result of impaired follicle development, oestrogen production becomes increasingly irregular, even in apparently ovulatory cycles. This was confirmed in the study of Dennerstein et al. [11], who found oestradiol concentrations of <100 pmol/l in 9% of women with regular menstrual cycles who were undergoing the menopausal transition. Inhibin could not be detected in 28% of these cycles, and FSH concentrations were elevated in 6.7%.

The increase in FSH concentrations reduces oocyte maturation time, which causes a shortening of cycle length. At other times there may be insufficient oestradiol production from the follicle to trigger an LH surge, and the failure of ovulation may delay menstruation. Eventually there are no follicles able to respond to the increasing concentrations of gonadotropins, and in the presence of low concentrations of oestradiol, the menopause follows. After menopause, the increase in FSH concentrations is relatively greater than that of LH, with FSH levels increasing 10–15 times, whereas concentrations of LH are only three to five times higher [12].

Types of contraception

Although all forms of contraception are available to couples where the female partner is perimenopausal, certain methods may be more suitable for women in this age group on medical grounds, whilst other methods may have no medical advantage but may simply be more convenient or more acceptable. After the age of 40, women become less likely to use contraception, but those who do so will more frequently undergo sterilization and are less likely to use oral contraceptives than younger women [13].

Sterilization

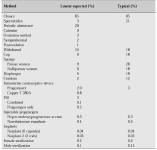

Sterilization is the most commonly used of all methods of contraception [14]. In the USA, approximately 15% of couples choose tubal sterilization and 12% vasectomy [15]. In the UK, over 40% of couples choose sterilization when the female partner is over 40 years of age [16]. Both tubal sterilization and vasectomy are safe and effective methods of contraception and are suitable options for couples who have completed their family. Tubal sterilization has been reported to have a lowest expected failure rate of 0.2% during the first year and a typical failure rate of 0.4% (Table IV) [17].

Sterilization has an advantage over contraceptive methods which must be used on a regular basis, and has few unwanted effects. It can be performed in women by the use of clips or bands, or by tubal resection, ligation or cautery. This can be done under general or regional anaesthesia, often in an outpatient or day care setting.

The main risks of the procedure involve the immediate problems of the anaesthetic and the operation itself. The report of the 1991 membership survey of the American Society of Gynecologic Laparoscopists described a complication rate from laparoscopic sterilization (defined as the number of cases requiring laparotomy) of 1.4/1000 procedures [18]. These are similar to our local figures, where the complication rate for laparoscopic sterilizations performed in Hong Kong in 1994 was 1/896 (0.1%), which was lower than that for diagnostic laparoscopy (62/2991; 2.1%) [7]. Apart from the operative risks, it has been suggested that tubal sterilization may increase the chance of subsequent menstrual disturbances. The evidence is contradictory, however, as dysfunctional uterine bleeding is more common with advancing age, and is especially likely to affect perimenopausal women. The balance of evidence suggests that the association between sterilization and menstrual disorders is probably coincidental [19], and this is not thought to be a valid reason for choosing an alternative method of contraception.

The chance of a perimenopausal woman regretting her decision to have a permanent form of contraception is less than that of a younger woman, and the likelihood of a failed procedure also appears to be lower. In a recent prospective cohort study of 10,685 women who had undergone tubal sterilization in the USA, the highest failure rates over a period of 8–14 years of follow-up were recorded in women who had been sterilized at a younger age (bipolar coagulation 54.3/1000, clip application 52.1/1000) [20]. However, in the event of a change of mind, success rates for reversal of sterilization are still high, with one study reporting a cumulative intrauterine pregnancy rate of 51.4% over 2 years in women aged 40 years or more [21].

Table IV: Lowest expected and typical percentages of accidental pregnancy in the USA during the first year of use of a method [17].

Oral contraceptives

Oral contraception is becoming an increasingly more popular form of birth control for healthy perimenopausal women as the safety of this method has become well established, especially for women who are non-smokers and who have no cardiovascular risk factors. Although oral contraceptives have some adverse effects, they also provide benefits apart from the contraceptive action which may have a favourable effect on the health of a perimenopausal woman.

There are a number of reasons why the use of oral contraceptives has gained in popularity in recent years, particularly in older women. Firstly, the doses of sex steroids in combined oral contraceptive pills are now much lower than those of the preparations which were available in the 1960s. Secondly, increased education has resulted in the screening out of many women at greatest risk of complications from oral contraceptive use. In addition, there has also been a substantial overall decline in the number of young women suffering from myocardial infarction and stroke, and this may also have had a favourable influence on safety figures [22].

Oral contraceptives are extremely effective when properly used. The failure rate of the new multiphasic and low-dose monophasic combination pills is approximately 0.1% per annum under ideal circumstances, and 3.0% per annum in unselected users (Table IV). The lower-dose preparations require that the tablet be taken at the same time each day, and this time restraint is even more strict for the progestogen-only pills.

Progestogen-only oral contraceptives may be considered for perimenopausal women who smoke or who have other contraindications to oestrogen use, or who suffer oestrogen-related side effects. Cycle control is not as good as with combined oral contraceptives, and an irregular bleeding pattern is the main reason for discontinuation of treatment. This may make this form of contraception unsuitable for many perimenopausal women [23].

Adverse effects of oral contraceptives on perimenopausal women

The results of various studies published in the 1970s showed that users of contraceptive pills containing more than 50 mg ethinyloestradiol were at a higher risk of developing venous thrombosis, myocardial infarction and stroke [24, 25]. This particularly applied to women over 35 years of age who were smokers or who had other cardiovascular risk factors [26]. As a result, lower-dose formulations became available which had fewer adverse effects but which, if used properly, were equally effective in providing contraception. Studies since then from both the USA and the UK have failed to show any significant increase in the risk of myocardial infarction in healthy users of modern oral contraceptives [27–29].

Current data suggest that the risk of venous thrombosis is mainly related to oestrogen dose, with a clinically significant cut-off level of 50 mg ethinyloestradiol. A slightly greater risk of thrombosis may also be present with 30 mg doses [30], but this represents only a minimal increase as it translates into one additional death per one million users per year with oral contraceptives compared with users of intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUDs) [31]. Data from the WHO Collaborative Studies of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception [32, 33] and the General Practice Research Study [34] have shown no increase in mortality from venous thrombosis or stroke in low-dose contraceptive users.

The WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception 1996 [32] investigated the risk of stroke in association with current use of combined oral contraceptives in 697 cases and 1962 age-matched controls from 21 centres in Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America (Table V). The risk of stroke was increased in users of oral contraceptives in both developed and developing countries. The adjusted odds ratio for ischaemic stroke in current users of oral contraceptives was 3.55 (2.13–5.92) in Asian women, which was higher than that of all other regions. Odds ratios were lower in women under 35 years of age who were non-smokers and who had no history of hypertension.

Table V: Odds ratios of ischaemic stroke in relation to combined oral contraceptive use by region [33].

The WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception 1995 [33] also examined the risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolic events and/or pulmonary embolism in users of oral contraceptives in the same centres as the study on the risk of stroke (Table V). Oral contraceptive use was associated with an increased risk of thrombotic events in European (OR 4.15 [3.09–5.57]) and in non-European countries (OR 3.25 [2.59–4.08]). In Asian women, the odds ratio was 7.30 (3.39–15.72), which was the highest of all of the developing countries and also higher than in Europe.

Most recently, the safety issue relating to the risk of venous thrombosis in users of oral contraceptives containing third-generation progestogens received widespread attention even before the publication of four studies suggesting that the risk of thrombosis was higher with these progestogens. These studies were conducted in the UK and in Europe [34–37] and prompted a warning from the Committee on Safety of Medicines to all doctors in the UK and later in some European countries about the safety of these oral contraceptives. Despite evidence suggesting an increased risk of thrombosis with third- rather than second-generation progestogens, a casual relationship was not established, and it has been suggested that a selection bias may have influenced these results [38]. Interpretation of these data remains controversial, and whilst the risk of thromboembolism may be slightly increased, the incidence is low, and is less than that associated with pregnancy.

Other factors to be considered in perimenopausal women are the effects of oral contraceptives on hypertension and the lipid profile. Current evidence suggests that low-dose oral contraceptives may cause an increase in blood pressure in a small proportion of users, but this appears to apply more to the monophasic than the multiphasic preparations. The reported increases are minor and have not been of clinical significance [39]. Whilst the use of contraceptives containing the older, higher-dose progestogens was associated with atherogenic changes in the lipid profile, no adverse effects have been found with those preparations containing the third-generation progestogens, and these may actually provide favourable lipid changes [40]. However, all combined oral contraceptives tend to cause an increase in concentrations of triglycerides, and as these may be a greater risk factor for atherosclerosis in women than in men, triglyceride concentrations should be carefully monitored after the commencement of treatment in those women who have borderline or elevated levels before treatment.

Diabetes mellitus is another disease which is more likely to affect women who are perimenopausal. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes can manifest itself in younger women, but is more commonly seen after the age of 40 years. Impaired glucose tolerance has been reported in 8–10% of women aged 20–40 years, and with advancing age, 3% per year will develop diabetes [41]. Whilst there is evidence to suggest that even the low-dose formulations increase insulin resistance [42], oral contraceptive use does not appear to increase the subsequent risk of developing diabetes [43]. Oral contraceptives containing the newer progestogens have less effect on insulin production as reflected on glucose tolerance testing [44]. Therefore, whilst young women who are insulin-dependent can use low-dose oral contraceptives without increasing their risk of diabetic retinopathy or nephropathy, these oral contraceptives are not recommended for perimenopausal women because of their higher cardiovascular risk.

There is no consistent evidence to show that breast cancer is more common in perimenopausal users of oral contraceptives [45]. Other risk factors such as nulliparity, a history of benign breast disease or a family history of breast carcinoma are more important than a history of oral contraceptive use. Although the risk of breast cancer may be increased in women who first take the pill at a young age and continue to use oral contraception for long periods of time [46], this may well not apply to the perimenopausal woman. There is, in fact, some evidence to suggest that oral contraceptives are protective against breast cancer in women diagnosed between 45 and 54 years of age compared with those diagnosed at a younger age [47].

Beneficial effects of oral contraceptives on perimenopausal women

The use of oral contraceptives can provide a number of benefits for otherwise healthy perimenopausal women who are non-smokers. The increased frequency of anovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding in perimenopausal women has already been mentioned. Oral contraceptives provide good cycle control and reduce the volume of bleeding in women with this condition. In addition, they prevent endometrial hyperplasia and they reduce the risk of endometrial carcinoma by at least 50% with more than 12 months of use [48]. Oral contraceptives also provide protection against ovarian carcinoma. The magnitude of the reduction in risk is less than that with endometrial carcinoma, but the effect persists for up to 15 years after discontinuation of treatment [48, 49]. Other studies have suggested an increase in the incidence of dysplasia and carcinoma of the cervix in users of oral contraceptives, but this may be influenced by other factors such as the number of sexual partners [50, 51].

As far as benign conditions are concerned, one of the most common gynaecological disorders to affect perimenopausal women is uterine fibroids. The risk of developing uterine fibroids appears to be unaffected by the use of low-dose oral contraceptives [52], and for those women with uterine fibroids and menorrhagia, the use of oral contraceptives may reduce the volume of menstrual bleeding [53].

Perimenopausal women may especially benefit from the protection against osteoporosis provided by oral contraceptives. Osteoporosis is a well-recognized consequence of the hypo-oestrogenic state, and the rate of bone loss is highest near to the time of the menopause. Reduced concentrations of oestradiol in perimenopausal women predispose to the development of osteoporosis, but bone loss may be prevented by oral contraceptive use. Corson [54] reviewed the results of 15 studies on the effect of oral contraception on bone mineral density. Whilst these studies differed in the doses of contraceptives, the duration of use and the method of bone density measurement, a positive association between oral contraceptive use and bone density was found in eight studies and no association in the remainder. It was concluded that premenopausal users of oral contraceptives had a 2–3% higher bone density than non-users at the time of the menopause, but that the clinical importance of this finding could not be determined.

Barrier methods

Condoms, diaphragms, caps and spermicides are relatively cheap methods of contraception which do not carry any special advantages for perimenopausal compared with younger women. One of their main benefits is protection against sexually transmitted diseases, especially the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It has been estimated that around 120 million people will be infected with HIV by the year 2000, and the majority of these will be from Africa, Latin America, India and South-East Asia [55]. Perimenopausal women are equally at risk of contracting the virus, and this factor may make condoms the safest method in many of the developing countries. Other advantages of condoms are that they are usually easy to obtain, are a reversible method of contraception and are comparatively cheap. Diaphragms have a relatively high failure rate, but they are more commonly used by older women with a lower rate of natural fertility [56].

Intrauterine contraceptive devices

Recent studies have suggested that the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease in women using IUDs is related more to the life style of the user rather than to the device itself [57], and this is likely to increase the acceptance of this method of contraception. IUDs have the advantages of being reversible and not needing frequent replacement. They are also highly effective, with a lowest expected failure rate of 0.8–2.0% during the first year of use and a typical failure rate of up to 3% (Table IV).

The relatively new IUD which releases 20 mg levonorgestrel each day may be particularly useful for the perimenopausal woman. The most common indication for removal of this device is amenorrhoea [58], which is unlikely to be viewed as a disadvantage by perimenopausal women. The levonorgestrel IUD is also associated with fewer episodes of prolonged bleeding, and the constant release of progestogen protects against endometrial hyperplasia. Women who use this type of IUD have been reported to have an 86% reduction in menstrual blood loss in the first 3 months of treatment, and the volume continues to decrease with longer duration of use [59]. Since they also have high efficacy and are a long-lasting form of contraception, they may be especially suitable for perimenopausal women.

Injectable contraceptives

The most widely available injectable contraceptive is depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera). This injectable progestogen acts by inhibiting ovulation, and a single 150 mg dose administered intramuscularly produces pharmacological concentrations of progestogen which persist for 3–4 months. It is also a highly effective method of contraception, with a lowest expected failure rate of 0.3% in the first year of use and a typical failure rate also of 0.3% [17]. The main problem with this method is that of irregular vaginal bleeding, and this may make it unsuitable for many perimenopausal women. Irregular bleeding causes up to 25% of women to discontinue treatment within the first year of use [60]. However, problems with irregular bleeding diminish with time, and up to 50% of women become amenorrhoeic after 1 year [61]. Apart from this, medroxyprogesterone acetate has relatively few side effects, and the possible delay in fertility after the discontinuation of treatment is rarely a problem for perimenopausal women. Whilst this method provides protection against endometrial carcinoma, perimenopausal women do not receive the advantages offered by a preparation which contains oestrogen, such as protection against osteoporosis [62].

Contraceptive implants

The sustained-release levonorgestrel contraceptive implant (Norplant) consists of six Silastic implants, each of which contains 36 mg levonorgestrel. A newer preparation consists of two rods containing a total of 70 mg levonorgestrel (Norplant-2), and these are easier to insert and to remove than the older implant. They act by inhibiting ovulation and are highly effective, with lowest expected as well as typical failure rates of 0.2% in the first year (Table IV). Levonorgestrel concentrations with Norplant peak at 0.4–0.5 ng/ml, but decrease to around 0.25 ng/ml after 5 years, which is the recommended duration of use [63]. Whilst Norplant is highly effective, skill is required to insert the implants and also to remove them if problems occur. The most common side effect leading to discontinuation of treatment is that of irregular bleeding, which means that this is another form of contraception which will be unsuitable for some perimenopausal women. Over 5 years only 5–10% of women become amenorrhoeic [64], and abnormal bleeding patterns develop in up to 80% of users [65]. The advantages for perimenopausal women are the low incidence of metabolic side effects and the long duration of action. Although Norplant is associated with a high incidence of irregular bleeding, it is not usually heavy, and for a perimenopausal woman whose only preceding problem has been menorrhagia, the use of Norplant may reduce the volume of blood loss and protect against anaemia [66].

Conclusion

There are no clearly established guidelines for when it is safe for a perimenopausal woman to discontinue contraception. Whitehead and Godfree [67] suggested that contraception should be continued for women who are 50 years or older until after 1 year of amenorrhoea, and for younger women, for a period of 2 years. If a perimenopausal woman is using oral contraceptives, it may be advisable to change to another method for a few months at around 50 years of age before measuring gonadotropin concentrations to determine her menopausal status. For users of both hormonal and non-hormonal methods, the time at which it is safe to discontinue contraception provides a suitable opportunity to discuss the risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy for the management of the menopause.

References

1. World Health Organization. Research on the menopause. WHO Tech Rep Ser 1981; 670: 8–10.

2. World Health Organization. Research on the menopause in the 1990s. WHO Tech Rep Ser 1996; 866: 13.

3. Sulak PJ, Haney AF. Unwanted pregnancies: understanding contraceptive use and benefits in adolescents and older women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993; 168: 2042–8.

4. Potts DM, Crane SF. Contraceptive delivery in the developing world. Br Med Bull 1993; 49: 27–39.

5. Lande RE, Geller JS. Paying for family planning. Popul Rep Ser J 1991; 39: 1–31.

6. The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong. Contraceptive methods used by all birth control clients in 1994 and 1995. The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong Annual Report, 1995–96; 32.

7. HKCOG territory-wide audit in obstetrics and gynaecology. Hong Kong: Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 1994; 75–83.

8. Richardson SJ, Senikas V, Nelson JF. Follicular depletion during the menopausal transition: evidence for accelerated loss and ultimate exhaustion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987; 65: 1231–7.

9. Metcalf MG. The approach of menopause: a New Zealand study. N Z Med J 1988; 101: 103–6.

10. Lee SJ, Lenton EA, Sexton L, Cooke ID. The effect of age on the cyclical patterns of plasma LH, FSH, oestradiol and progesterone in women with regular menstrual cycles. Hum Reprod 1988; 3: 851–5.

11. Dennerstein L, Smith AM, Morse C et al. Menopausal symptoms in Australian women. Med J Aust 1993; 159: 232–6.

12. Burger HG. Reproductive hormone measurements during the menopausal transition. In: Berg G, Hammar M, eds. The modern management of the menopause. Carnforth, UK: Parthenon, 1994; 103–7.

13. Oddens BJ, Visser AP, Vemer HM et al. Contraceptive use and attitudes in Great Britain. Contraception 1994; 49: 73–86.

14. Parker-Mauldin W, Segal S. Prevalence of contraceptive use: trends and issues. Stud Fam Plann 1988; 6: 335.

15. Kaunitz AM, Illions EH, Jones JL, Sang LA. Contraception. A clinical review for the internist. Med Clin North Am 1995; 79: 1377–1409.

16. Guillebaud J. Contraception for women over 35 years of age. Br J Fam Plann 1992; 17: 115–8.

17. Trussell J, Hatcher RA, Cates W Jr et al. Contraceptive failure in the United States: an update. Stud Fam Plann 1990; 21: 51–4.

18. Peterson HB, Hulka JF, Phillips JM, Surrey MW. Laparoscopic sterilization. American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists 1991 Membership Survey. J Reprod Med 1993; 38: 574–6.

19. Liskin L, Rinehart W, Blackburn R, Rutledge AH. Minilaparotomy and laparoscopy: safe, effective and widely used. Popul Rep Ser C 1985; 9: 125–67.

20. Peterson HB, Xia Z, Hughes JM et al. The risk of pregnancy after tubal sterilization: findings from the US Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174: 1161–8.

21. Dubuisson JB, Chapron C, Nos C et al. Sterilization reversal: fertility results. Hum Reprod 1995; 10: 1145–51.

22. Fortney JA. Oral contraceptives for older women. IPPF Med Bull 1990; 24: 3–4.

23. Broome M, Fotherby K. Clinical experience with the progestogen-only pill. Contraception 1990; 42: 489–95.

24. Mann JI, Vessey MP, Thorogood M, Doll SR. Myocardial infarction in young women with special reference to oral contraceptive practice. Br Med J 1975; 2: 241–5.

25. Berel V. Mortality among oral contraceptive users. Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. Lancet 1977; ii: 727–31.

26. Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. Incidence of arterial disease among oral contraceptive users. J R Coll Gen Pract 1983; 33: 75–82.

27. Porter JB, Jick H, Walker AM. Mortality among oral contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol 1987; 70: 29–32.

28. Croft P, Hannaford PC. Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in women: evidence from the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. Br Med J 1989; 298: 165–8.

29. Thorogood M, Mann J, Murphy M, Vessey M. Is oral contraceptive use still associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991; 98: 1245–53.

30. Lidegaard ¯. Oral contraception and the risk of a cerebral thromboembolic attack: results of a case-control study. Br Med J 1993; 306: 956–63.

31. Hirvonen E, Idanpaan-Heikkila J. Cardiovascular death among women under 40 years of age using low-estrogen oral contraceptives and intrauterine devices in Finland from 1975 to 1984. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990; 163: 281–4.

32. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Ischaemic stroke and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international, multicentre, case-control study. Lancet 1996; 348: 498–505.

33. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international, multicentre, case-control study. Lancet 1995; 346: 1575–82.

34. Jick H, Jick SS, Gurewich V et al. Risk of idiopathic cardiovascular death and nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives with differing progestogen components. Lancet 1995; 346: 1589–93.

35. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Effect of different progestins in low oestrogen oral contraceptives on venous thrombosis. Lancet 1995; 346: 1582–8.

36. Bloemenkamp KWM, Rosendaal FR, Helmerhorst FM et al. Enhancement by factor V Leiden mutation of risk of deep-vein thrombosis associated with oral contraceptives with differing progestagen components. Lancet 1995; 346: 1593–6.

37. Spitzer WO, Lewis MA, Heinemann LAJ et al. Third generation oral contraceptives and risk of venous thromboembolic disorders: an international case-control study. Br Med J 1996; 312: 88–90.

38. Lidegaard ¯, Milsom I. Oral contraceptives and thrombotic diseases: impact of new epidemiological studies. Contraception 1996; 53: 135–9.

39. Oral contraception. In: Speroff L, Darney P, eds. A clinical guide for contraception. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1996; 55.

40. Gevers Leuven JA, Dersjant-Roorda MC, Helmerhorst FM et al. Estrogenic effect of gestodene-desogestrel-containing oral contraceptives on lipoprotein metabolism. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990; 163: 358–62.

41. Corson SL. Contraception for women with health problems. Int J Fertil 1996; 41: 77–84.

42. Godsland IF, Crook D, Simpson R et al. The effects of different formulations of oral contraceptive agents on lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. N Engl J Med 1990; 323: 1375–81.

43. Hannaford PC, Kay CR. Oral contraceptives and diabetes mellitus. Br Med J 1989; 299: 1315–6.

44. Becker H. Supportive European data on a new oral contraceptive containing norgestimate. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl 1990; 152: 33–9.

45. World Health Organization. Oral contraceptives and neoplasia. Research on the menopause. WHO Tech Rep Ser 1992; 817: 8–12.

46. Rushton L, Jones DR. Oral contraceptive use and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of variations with age at diagnosis, parity and total duration of oral contraceptive use. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992; 99: 239–46.

47. Wingo PA, Lee NC, Ory HW et al. Age-specific differences in the relationship between oral contraceptive use and breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1991; 78: 161–70.

48. Vessey MP, Painter R. Endometrial and ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives — findings in a large cohort study. Br J Cancer 1995; 71: 1340–2.

49. The cancer and steroid hormone study of the CDC and NICHD. The reduction in risk of ovarian cancer associated with oral-contraceptive use. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 650–5.

50. Delgado-Rodriguez M, Sillero-Arenas M, Martin-Moreno JM, Galvez-Vargas R. Oral contraceptives and cancer of the cervix uteri. A meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1992; 71: 368–76.

51. Gram IT, Macaluso M, Stalsberg K. Oral contraceptive use and the incidence of cervical epithelial neoplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 167: 40–4.

52. Parazzini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of uterine fibroids. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 79: 430–3.

53. Friedman AJ, Thomas PP. Does low-dose combination oral contraception use affect uterine size or menstrual flow in premenopausal women with leiomyomas? Obstet Gynecol 1995; 85: 631–5.

54. Corson SL. Oral contraceptives for the prevention of osteoporosis. J Reprod Med 1993; 38: 1015–20.

55. Potts M, Anderson R, Boily MC. Slowing the spread of human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries. Lancet 1991; 338: 608–13.

56. Vessey MP, Lawless M, Yeates D. Efficacy of different contraceptive methods. Lancet 1982; i: 841–2.

57. Lee NC, Rubin GL, Borucki R. The intrauterine device and pelvic inflammatory disease revisited: new results from the Women’s Health Study. Obstet Gynecol 1988; 72: 1–6.

58. Chi IC. The TCu-380A, (AG), MLCu375, and Nova-T IUDs and the IUD daily releasing 20 mg levonorgestrel — four pillars of IUD contraception for the nineties and beyond? Contraception 1993; 47: 325–47.

59. Andersson K, Rybo G. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in the treatment of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1990; 97: 690–4.

60. Cromer BA, Smith RD, Blair JM et al. A prospective study of adolescents who choose among levonorgestrel implant (Norplant), medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera), or the combined oral contraceptive pill as contraception. Pediatrics 1994; 94: 687–94.

61. Belsey EM. Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception. Contraception 1988; 38: 181–206.

62. Cundy T, Evans M, Roberts H et al. Bone density in women receiving depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. Br Med J 1991; 303: 13–6.

63. Brache V, Alvarez-Sanchez F, Faundes A et al. Ovarian endocrine function through five years of continuous treatment with Norplant subdermal contraceptive implants. Contraception 1990; 41: 169–77.

64. Shoupe D, Mishell DR Jr, Bopp BL, Fielding M. The significance of bleeding patterns in Norplant implant users. Obstet Gynecol 1991; 77: 256–60.

65. Darney PD, Elizabeth A, Tanner S et al. Acceptance and perceptions of Norplant among users in San Francisco, USA. Stud Fam Plann 1990; 21: 152–60.

66. Nilsson CG, Holma P. Menstrual blood loss with contraceptive subdermal levonorgestrel implants. Fertil Steril 1981; 35: 304–6.

67. Whitehead MI, Godfree V. Hormone replacement therapy: your questions answered. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1992; 215.