First Consensus Meeting on Menopause in the East Asian Region

The attitudes of postmenopausal women towards hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and the effects of HRT on lipid profiles

Jin Yong Lee and Chang Suk Suh

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, College of Medicine, Seoul National University, Republic of Korea

Introduction

The menopause marks a time of dramatic hormonal and often social change for women. In 1960, the world population of women aged over 60 was below 250 million, but it is estimated that in the year 2030, 1.2 billion will be peri- or postmenopausal, and that this total will increase by 4.7 million a year. It is also estimated that in developed countries, women now aged 50 can be expected to live for a further 30 years. Because of these predicted changes in population structure, physicians are beginning to see the menopause not as a negligible natural phenomenon but as a major public health problem.

With improved medical care and a diminishing birth rate, the proportion of elderly people in Korea has also been continually increasing since 1960. By the turn of the century, the peri- and postmenopausal population over 50 will reach 10 million (20.1%). In spite of the well-known benefits of receiving hormone replacement therapy (HRT), however, the percentage of postmenopausal women in Korea undergoing such treatment is still quite low. This paper describes the attitudes of postmenopausal women towards receiving hormone therapy, and the impact of progestogen on lipid profiles during oestrogen replacement therapy.

Attitudes of postmenopausal women towards hormone replacement therapy

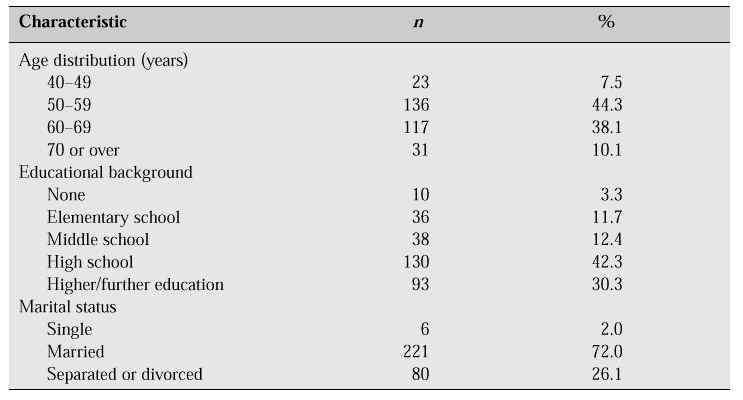

HRT has an established role in improving menopausal symptoms, reducing cardiovascular risk and preventing osteoporosis. However, compliance with HRT is not as good as expected. It is difficult to know with any certainty the attitude of Korean postmenopausal women towards HRT because there has been no large population-based survey in Korea. However, we have carried out our own assessment of menopausal women’s attitudes towards the menopause and HRT to uncover some factors that might increase its use. Our group carried out a survey at two churches located in the Seoul metropolitan area between August 1993 and June 1994 [1]. We provided a questionnaire, and interviews were conducted with 307 postmenopausal women whose menopause had been either natural or surgically induced (Table I).

Table I: Characteristics of respondents [1].

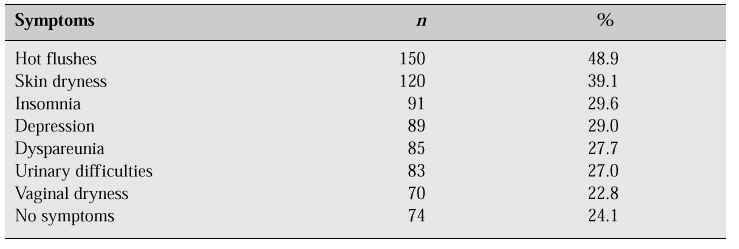

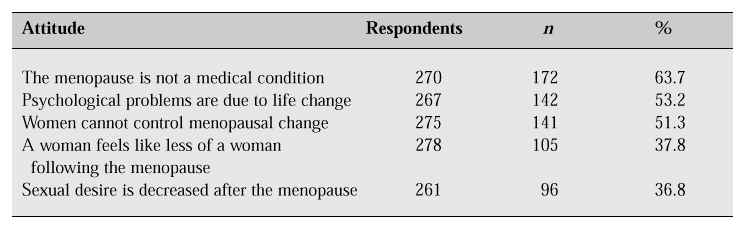

According to the results of our survey, more than three-quarters (75.9%) of the women had experienced menopausal symptoms (Table II). Hot flushes were the leading symptom, affecting 48.9% of the women. However, the incidence of vasomotor symptoms in Korean women is relatively lower than that in Western women. This finding may reflect the cultural and social background. Concerning their attitude towards the menopause, 63.7% of respondents did not perceive the menopause to be a medical condition but a part of the natural ageing process, 53.2% believed that psychological problems after the menopause are due to life changes, and 51.3% believed that women cannot control menopausal change (Table III).

Table II: Prevalence of menopausal symptoms [1].

Table III: Attitude towards the menopause [1].

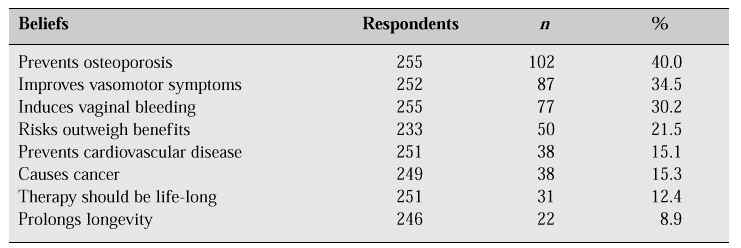

As many Korean women have been influenced by traditional Confucianism, most seem to accept the menopause as predestination. But interestingly, 40.0% of respondents were aware of the effectiveness of HRT in the prevention of osteoporosis, 34.5% believed that HRT improves vasomotor symptoms, yet only 15.1% were aware of the effectiveness of HRT in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. In addition, 15.3% of respondents were concerned about the risk of cancer, and 21.5% believed that the risks of oestrogen outweigh the benefits (Table IV).

Table IV: Knowledge about HRT [1].

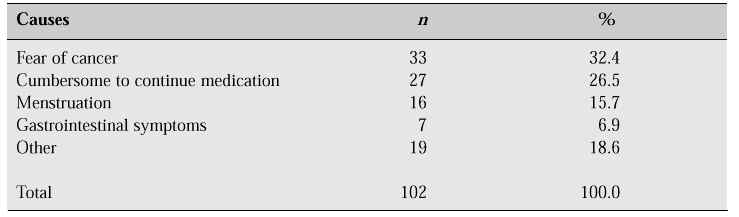

One hundred and twenty-four women (40.4%) had experienced HRT, a figure comparable with that found in the Framingham study [2] which reported that 32% of women between the ages of 50 and 59 years had used oestrogen after the menopause. However, among 124 women who had used HRT, only 17.7% continued to take HRT for more than 1 year at the time of the survey, and the main reasons for stopping HRT were fear of cancer in 32.4%, cumbersome to continue medication in 26.5%, reappearance of vaginal bleeding in 15.7%, gastrointestinal trouble in 6.9%, and 18.6% specified various reasons including weight gain and acne (Table V).

Table V: Reasons for discontinuing HRT [1].

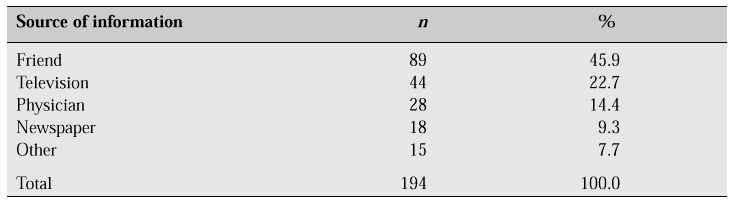

Most Korean women have experience of taking oral contraceptives during their reproductive years, and though the oestrogen dosage in postmenopausal HRT is considerably lower than that of oral contraceptives, the myth that oestrogen might cause some side effects seems to prevail among the general population. In contrast with the Ferguson study [3] which pointed out that the most important person affecting a woman’s decision regarding HRT is her physician, our survey revealed that 63.2% of respondents were aware of HRT at the time of the survey, but the information was obtained from friends in 45.9%, from television or the mass media in 32.0%, and from physicians in only 14.4% (Table VI).

Table VI: Sources of information about HRT [1].

Among the physicians who recommended HRT, gynaecologists accounted for 66.1%, followed by internists (17.7%), family doctors (8.0%) and orthopaedic surgeons (6.5%). This observation revealed that many physicians other than gynaecologists in Korea are still reluctant to recommend HRT to postmenopausal women. Our data suggest that a systematic educational approach to postmenopausal women as well as to physicians is required to influence postmenopausal women’s willingness to take HRT, and their misunderstandings should be resolved in order to increase compliance.

The impact of progestogen on lipid profiles during oestrogen replacement therapy

Cardiovascular disease was the leading cause of death (142.8/100 thousand population) in 1995 in Korea, and the mortality rate from cardiovascular disease was remarkably increased among elderly women (133.0 in the sixth decade, 445.2 in the seventh decade and 2046.6 in the eighth decade in 1995) [4]. In contrast with the West, 50% of deaths caused by cardiovascular disease were due to cerebrovascular accident, and 30% of such deaths were due to coronary heart disease.

The incidence of coronary heart disease depends on both age and sex. Before the menopause, the incidence in women is less than that in men among the same age group, but after the menopause, the incidence rates converge. This can be explained by oestrogen deficiency, which begins before the menopause. There is a considerable body of evidence to support a relationship between the occurrence of postmenopausal cardiovascular disease and oestrogen deficiency [5]. In women who underwent bilateral oophorectomy before the age of 35, the risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction was estimated to be approximately 7.2 times that of premenopausal women. Hysterectomy without the removal of both ovaries was only weakly associated with an increased risk. The data support the hypothesis that premature cessation of ovarian function increases the risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction [6].

Several studies have indicated that plasma high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol shows either no significant change or a gradual decrease after the menopause, while low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol shows an abrupt increase, suggesting a relationship between the plasma lipid profile and the menopause-related hormonal changes [7–9]. A 1% increase in total cholesterol, or LDL cholesterol, increases the risk of coronary heart disease by 2%; in contrast, a 1% decrease in HDL cholesterol increases the risk by 2–4.7% [10–12].

Oestrogen use by postmenopausal women has been associated with a decrease in the rate of coronary heart disease in a number of elegant epidemiologic studies [13]. The relative risk of coronary heart disease from these studies indicates that current hormone users may have a 50% lower risk than never-users. However, almost all the epidemiologic studies showing a protective effect of HRT on cardiovascular disease have studied women using oestrogen without the addition of progestogen. Recently, progestogens have been prescribed with oestrogen for women with an intact uterus, to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer from unopposed oestrogen. The benefits of oestrogen replacement therapy in reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease may be related in part to the change in serum lipoprotein concentrations, including an increase in HDL cholesterol and a reduction in LDL cholesterol [5]. Miller et al. [14] found that the oestrogen-induced increase in HDL cholesterol was attenuated by 14–17% with the addition of progestogen, but there was little change in LDL cholesterol. However, the effects of combined oestrogen-progestogen formulations on the lipid profile are not completely clear.

To assess the changes in lipid profile during oestrogen replacement therapy, we carried out a cross-sectional 1-year trial of conjugated equine oestrogen (Premarin 0.625 mg/day continuously) with and without cyclic progestogen (medroxyprogesterone acetate [MPA] 10 mg/day for 12 days) in 92 postmenopausal women [15]. Study subjects were divided into two groups: a Premarin group without a uterus (n = 48), and a Premarin-MPA group with an intact uterus (n = 44). The patient characteristics were comparable between the two groups (Table VII).

Table VII: Patient characteristics and lipid and lipoprotein levels by treatment group (mean ± SD).

Serum total cholesterol, triglyceride and HDL cholesterol levels in the fasting state were measured in all subjects before treatment and at 3-monthly intervals during treatment for 12 months. LDL cholesterol levels were calculated by the following standard formula:

LDL cholesterol = total cholesterol - HDL cholesterol - (triglyceride/5)

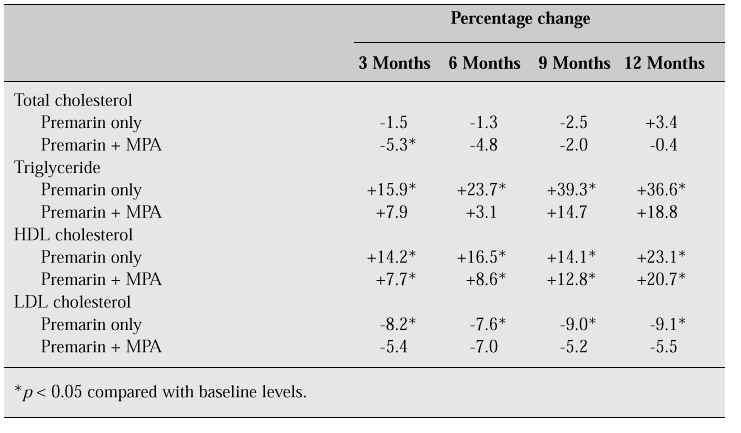

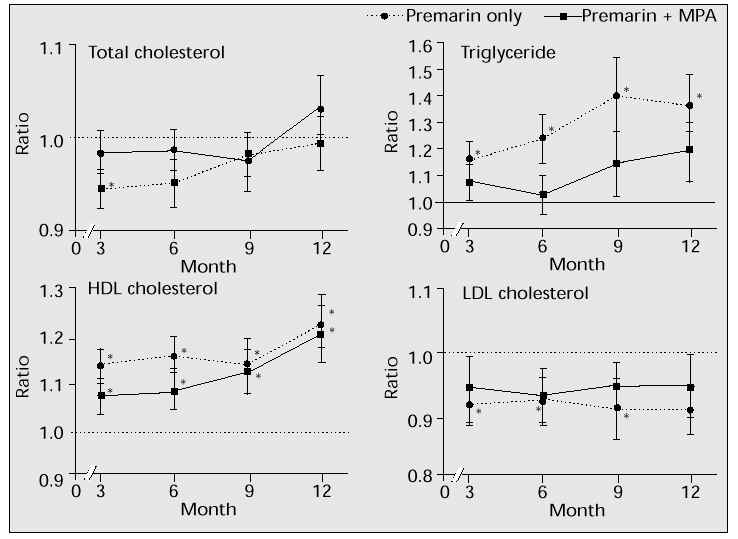

The values of post-treatment levels were compared with those of baseline levels. Table VIII and Figure 1 show the percentage changes in serum lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol levels during HRT in our study. In patients who received either Premarin only or Premarin + MPA, serum HDL cholesterol levels increased significantly throughout the treatment period. While the Premarin + MPA group showed a smaller increase in HDL cholesterol than the Premarin-only group at 3 and 6 months after treatment, there was no difference in increase in HDL cholesterol between the two groups after 12 months of treatment. Serum LDL cholesterol levels decreased significantly during 12 months of therapy in the Premarin-only group, but the Premarin + MPA group showed a lower decrease which was not statistically significant. Throughout the treatment period, the decrease in total cholesterol was of smaller magnitude, and there was no statistically significant change in either group. Serum triglyceride increased significantly in the Premarin-only group whereas it showed a non-significant increase in the Premarin + MPA group compared with the Premarin-only group. The percentage change in serum lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol after administration of Premarin only vs Premarin + MPA at 12 months of therapy was +23.1% vs +20.7% for HDL cholesterol, -9.1% vs -5.5% for LDL cholesterol, +3.4% vs -0.4% for total cholesterol, and +36.6% vs +18.8% for triglyceride. These data suggest that as the period of therapy is extended, the addition of progestogen does not negate the effect of oestrogen on lipid profiles.

Table VIII: Percentage changes in serum lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol levels by duration of HRT.

Fig. 1: Changes in serum lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol levels during oestrogen replacement therapy with or without MPA. *p < 0.05.

The results of our study generally agree with those of previously reported studies indicating that postmenopausal women treated with oestrogen replacement therapy show an increase in HDL cholesterol and triglyceride, and a decrease in LDL cholesterol [5]. Furthermore, the lowering of HDL cholesterol by progestogen may be time-dependent with a less negative effect after prolonged use [16].

Conclusions

In the developed countries, the increased proportion of postmenopausal women is a continuing phenomenon. The ovaries of postmenopausal women cease to function which results in tremendous hormonal changes. Cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women abruptly increases and equals that seen in men of a corresponding age. Numerous studies have indicated that oestrogen replacement therapy can prevent coronary heart disease by changing lipid profiles and through other effects on blood vessels. Yet, despite the well-known benefits of HRT, compliance among postmenopausal women is still quite low. However, this might be because of either patients’ false beliefs or practitioners’ negative attitudes towards long-term HRT, based on the fear of cancer. To date, though, most investigators have reported that the beneficial effects of HRT are greater than the adverse effects. In order to improve quality of life for postmenopausal women, an approach which involves the continuous and systematic education of both practitioners and postmenopausal women themselves is required.

The evidence that oestrogen replacement therapy protects against cardiovascular disease is quite strong. Although the biological data regarding the effects of adding progestogen in HRT on cardiovascular protection are not clear, there is a considerable body of evidence that women taking oestrogen with progestogen appear to have a similar decrease in risk to those taking oestrogen alone. Our recent study indicates that progestogen together with oestrogen in the postmenopausal woman does not seem to negate the beneficial effect of oestrogen alone on the lipid profile.

Further studies are needed into the novel progestogens with minimal HDL cholesterol-lowering effect, the possible antioxidative properties of oestrogen and the metabolic link between the lipoprotein and homeostatic risk factor system, as suggested by Tikkanen [17].

References

1. Kim JG, Kim JW, Kim SH, Lee JY. A survey of menopausal women’s attitude to the menopause and hormone replacement therapy. Korean J Menopause 1995; 1: 42–50.

2. Wilson PWF, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. Postmenopausal estrogen use, cigarette smoking and cardiovascular morbidity in women over 50: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med 1985; 313: 1038–43.

3. Ferguson KJ, Hoegh C, Johnson S. Estrogen replacement therapy. A survey of women’s knowledge and attitudes. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149: 133–6.

4. Mortality rate in 1995, Seoul, Korea. Seoul: National Statistics Office, 1997.

5. Bush TL, Miller VT. Effect of pharmacologic agents used during the menopause. Impact on lipids and lipoproteins. In: Mishell D, ed. The menopause: physiology and pharmacology. Chicago, IL: Year Book Medical Publishers, 1986; 187.

6. Rosenberg L, Hennekens CH, Rosner B et al. Early menopause and the risk of myocardial infarction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981; 139: 47–51.

7. Kannel WB. Nutrition and occurrence and prevention of cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Nutr Rev 1988; 46: 68–78.

8. Matthews KA, Meilahn E, Kuller LH et al. Menopause and risk factors for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1989; 321: 641–66.

9. Jensen J, Nilas L, Christriansen C. Influence of menopause on serum lipids and lipoproteins. Maturitas 1990; 12: 321–31.

10. Lerner DJ, Kannel WB. Patterns of coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality in the sexes. A 26-year follow up of the Framingham population. Am Heart J 1986; 111: 383–90.

11. Chen Z, Peto R, Collins R et al. Serum cholesterol concentration and coronary heart disease in a population with low cholesterol concentrations. Br Med J 1991; 303: 276–82.

12. Manson JE, Tosteson H, Ridker PM et al. The primary prevention of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 1406–16.

13. Grodstein F, Stampfer M. The epidemiology of coronary heart disease and estrogen replacement in postmenopausal women. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1995; 38: 199–210.

14. Miller VT, Muesing RA, LaRosa JC et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen with and without three different progestogens on lipoproteins, high-density lipoprotein subfractions, and apolipoprotein A-1. Obstet Gynecol 1991; 77: 235–40.

15. Choi YM, Kim JG, Lee JY. Long-term impacts of oral progesterone (medroxyprogesterone acetate) on the levels of serum lipid and lipoproteins during estrogen replacement therapy in postmenopausal women. Korean J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 38: 97–104.

16. Paganini-Hill A, Dworsky R, Krauss RM. Hormone replacement therapy, hormone levels, and lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations in elderly women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174: 897–902.

17. Tikkanen MJ. The menopause and hormone replacement therapy: lipids, lipoproteins, coagulation and fibrinolytic factors. Maturitas 1996; 23: 209–16.